Cover photo, ironically, generated by AI.

The conceptions surrounding innovation and human nature seem almost indistinguishable. The image of humanity is nothing but a representation of our ability to meticulously manipulate the world around us. Our default modality bears no resemblance to the standard operations of an animal creature, rather bound by the complexions of our own creation. We have mastered the seas with our ships, littered the skies with our airplanes, and dominated the lands with our infrastructure. Human innovation and drive is a ceaseless spectacle, for better or for worse.

AI is promised to be the turning point of this time period. As impactful as the internet, the telephone, the motor vehicle, and the like, the impending hope for AI sits at the crux of the question: what’s it actually going to do?

Artificial Intelligence has been beaten to death as the latest silicon valley buzzword. With Microsoft, the owner* of OpenAI and the immensely popular ChatGPT, recently eclipsing $3 trillion dollars in market value, companies are inherently incentivized to “implement” AI with their products. “Implement” in quotes as the actual depth of many of these AI implementations are done in a last-ditch effort to gain angel investment (see Humane AI Pin). With companies, incentivized by markets, scrambling to adopt AI or be left in the past, it becomes difficult for the average person to keep up with what AI is.

*OpenAI’s corporate structure is complicated. A nice quick explainer video is here.

Terms like “Large Language Model”, “Multimodal”, and “Hallucination” leave consumers stranded, and defining these terms does not help us analyze the implications of AI. In it’s current state, artificial intelligence is not a live consciousness, or what researchers call “Artificial General Intelligence”. In simple terms, the AI isn’t “alive” as we would understand it. For the purposes of this article, I am assuming that AI will not grow to this level of intelligence, as that brings about a whole other set of moral implications.

A multitude of different AI tools have been released to the public for testing, experimentation, and deployment. For instance, ChatGPT is a highly effective tool for textual generation, analysis, and summaries, and is already being used by companies as a customer service agent, for example. Image-generation AI tools like DALL-E are effective at replacing stock images with purpose built generated photos (and memes too). Deepfake AI tools are only improving, and were recently used to impersonate Biden’s voice through robocalls to discourage primary voters. Just a few hours ago, OpenAI unveiled (but did not publicly release) Sora, which can dynamically create convincing video clips from text inputs. Other AI tools exist for all sorts of purposes, but the wide variation in these tools also makes it difficult to define AI.

Instead, I choose to define AI by its implications. Take the job of a low-level paralegal, for instance. No paralegal can possibly index the content of thousands of documents, emails, and other information provided during discovery in legal cases on their lonesome. That’s why law offices employ lots of paralegals in the first place. However, what if I could upload all my documents to an AI tool that would analyze them for legal inconsistency? This isn’t a far-fetched idea – it’s already being worked on. How many paralegals would be out of work if one AI tool (without labor costs, by the way) could replace the vast majority of their job? This is the kind of implication that I choose to define AI by: how will it change what we define as “work”? How many people will AI leave unemployed?

Opinions on the effects of technological revolutions vary greatly. In the vein of the Luddites, AI is poised to wipe away an innumerable number of jobs, with the government systems in place desperately unprepared to handle the vast and rapid unemployment that will ensue. On the other hand, there is the age-old idea that even as innovation destroys jobs, those same innovations create job markets that would have been impossible to imagine before said innovation. I do not have a firm foot in either camp. However, I am personally disgusted by humanities inability to cease innovation in the name of moral consideration. I find it repugnant that we, as a species, are constantly set on the idea that innovation breeds a better life. I am in fundamental disagreement with the idea that AI will bring about positive change, and I find myself amazed that there is no public consideration as to whether we, the people, even want this technology. I don’t. Many of my peers don’t. Even if you are bullish on the prospects of AI, a part of you must be concerned, and these concerns will go unanswered in the name of blind innovation and human shortsightedness. Remember that the world is all our creation, the good and the bad.

As this article comes to a close, I would like to pose a question to the reader. If humanity was reversed to a pre-agricultural period, would we be a more satisfied and fulfilled species? My answer is yes, and that answer provides the fundamental basis for my moral rejection of innovation at any cost. Nevertheless, I still exist and participate in a society that I fundamentally disagree with the existence of, and AI is but a reflection of this point. I hope that I am wrong, and that AI will bring about a series of wondrous positive changes. Nevertheless, my pessimism about human nature lends me to believe that AI will bring yet another wave of human deplorability and suffering.

Update: February 21, 2024

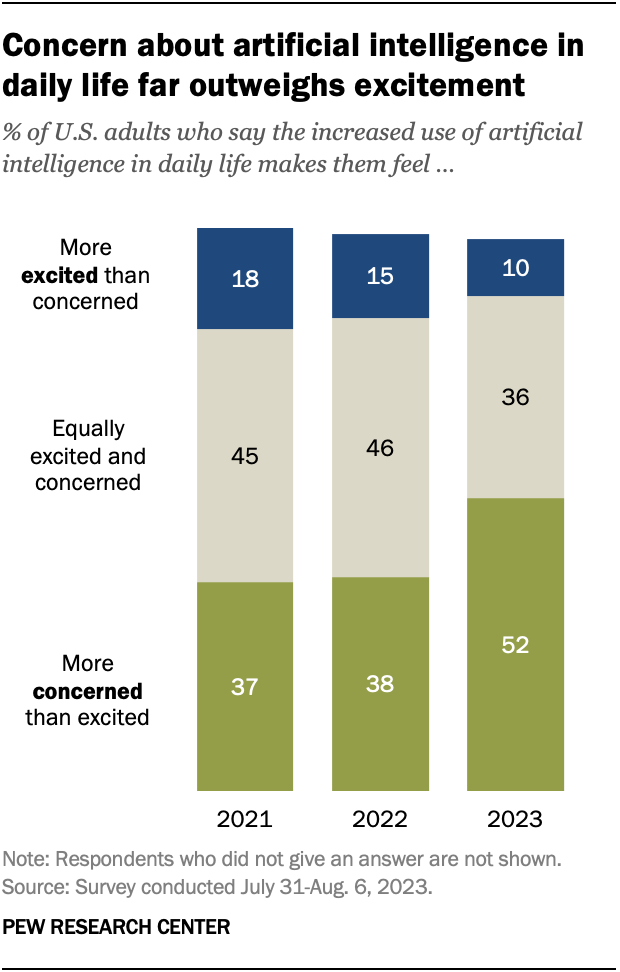

According to the Pew Research Center, the majority of Americans are now more concerned than excited about the prospects of AI.

Leave a Reply